I was on a long, quiet run. A long run is one that exceeds ten miles. A quiet run is one where I don’t listen to music or podcasts — where all that will sound like noise versus substance — where I set no time goal, focus on what’s around me, and let my mind run too. I told myself I’d be happy with ten, and set out conservatively because it was lazy Sunday.

The conditions were everything a New England runner could hope for on a November morning. The sun shone brightly and temperature allowed for ongoing exposure without a full UnderArmour bodysuit.

I convinced my legs by starting slow. However, it’s the brain that requires the most coaxing. Let me clarify. It’s the half of the brain that loves down blankets, TV, donuts, and hot drinks that demands seduction, but is always willing to celebrate with the hardworking, goal-oriented champion half. The anatomy of my head is the classic tale of the little red hen. Weather made the pursuit easier, along with the history that even the lazy lobe knows: you are going to love how this feels at the end.

We headed to Ashley Reservoir – the part that wanted to stay swaddled, and me. We breathed in the good air, and started to feel more like one. Ashley Reservoir is a gem of Holyoke, Massachusetts — a sanctuary, tucked a ways off the main road, like hidden treasure. I like to imagine a disoriented out-of-towner pulling into the drive to fiddle with her GPS then noticing the water at a distance. She gets out of her car with some trepidation because she, like many, has been told and sold on Holyoke’s reputation, but can’t resist the pull of the masterpiece that lies ahead, just beyond the gates…a path flanked by hundred foot tall evergreens leading to the water. It is so prodigious in scale, and the allure is too much. The GPS is forgotten, and now she is on a great adventure by foot, past the gates and down to the water to see what else is there. This is the wildest thing she’s done in months, nay, years. It’s just about a tenth of a mile, but when she arrives, she sees that the path turns left and right. She stares out at the water for just a few minutes, smiles at the discovery, and returns to her car… in a different place than when she parked.

Anyhow, I usually take a right where imaginary lady sees the path split. And perhaps unsurprisingly, it loops all the way back to the start. The view changes throughout. First the majestic evergreens, then trees on one side and water on the other, then water on both sides as trail turns to causeway.

The causeway has long had a hold on me. I first encountered it as a wee fourth grader, biking with my best friend. We flew across, awed by dead fish that had washed ashore. I had never seen such a thing. Not the dead fish, but this narrow, natural bridge that goes on and on. But like many places of childhood memory, I lost the causeway after the bike ride, and did not rediscover it until the first day of high school cross-country practice. This ranks in my top five for cool human experiences — losing something for a while and then finding it again, just as awesome.

Falling into a stride, the spell of the reservoir quickly took effect. I never get bored of its track. There is no shortage of natural occurrence for study, particularly with the change of seasons. On this day, the shorelines donned delicate ice skirts – with all the rocks and vegetation visible below – seemingly stationery, as if preserved behind glass. Mollusk shells lay scattered near the banks, a highlight of the exhibit. Upon first notice, I thought the gulls had grabbed long-distance takeout from the Atlantic, but was quickly enlightened to the existence of freshwater mussels.

I ran along. Thoughts of art and science and people flowed in and out of the now harmonious mind. I passed by the strange open dig site, where high school running mates played “king of the mountain” on the dirt heaps. (Holyoke High did not take any cross-country championships in my time there.) And then, the last trees before the mystical causeway, arching to usher you out onto the water. A walk of this unassuming, yet stately aisle could make even the most plebian feel royal… chosen… blessed. It is there for all, a quiet place of communion with nature, disguised by a driveway in the old mill town.

I don’t remember exactly what preoccupied my mind before seeing the bird, but my memory of the creature is pronounced, undoubtedly for the curiosity and emotion it evoked.

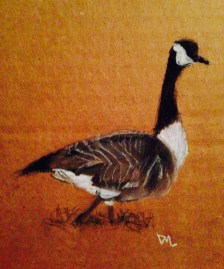

Not more than a quarter mile over the distinctive pass, a pack of gulls stood where land meets water — and among them, one goose.

Strange, I thought. Where are all your friends? It occurred to me that I hadn’t seen any other members of the notorious Canadian gang who force me to tread lightly in the spring, when small ones roam about. They’re a nasty lot – hissing at trespassers and shitting all over the sacred causeway. This one stood alone though – not as intimidating. I sensed that something was wrong.

Closer proximity confirmed my suspicion. There it was, contorted all out of place, a broken wing. I quickly understood. You couldn’t go with the rest, could you? I didn’t stop. What could I have done? But emotion erupted from deep within for a few moments before I shut it down, not wanting to explain to other runners.

My body keeps the Sunday pace, but mind races, spiraling into a thousand questions on the tiny brain of the goose. Are you scared, or angry? Do you feel at all? (Clearly impacted by animal cartoons of youth.) But can you sense that something’s wrong? Are you trying to adapt by hanging with the gulls? This stream of unanswered query goes on for roughly a half-mile, before the mental current finds new direction.

On the second loop though, the goose is still there. It has crossed the path, and now stands even closer to passersby. I look into its eyes and cry harder than the first time. Will it survive the winter? Will I see it again? I wanted to save it – to call animal rescue, bundle it up and take it home to the tub for the cold months. But as the lobes divorce again, some part up there suggests, “Well, this is nature,” like a know-it-all snob. Another part is not satisfied with her callousness.

I eat fowl, and have goose on Christmas Eve. But something about this one’s vulnerability got me. It couldn’t leave, like it was supposed to, like it perhaps needed to. It was stuck.

Hearing steps behind me, again, I quickly regained composure.

“Is everything okay ma’am,” I imagine, “But it can’t fly,” amidst sobs.

I run home and pull up the Cornell Lab of Ornithology website (my go-to for all fowl inquiries – because I have so many.)

I furiously skim for migration facts.

In winter, Geese can remain in northern areas with some open water and food resources even where temperatures are extremely cold. Geese breeding in the northernmost reaches of their range tend to migrate long distances to winter in the more southerly parts of the range, whereas geese breeding in southern Canada and the conterminous United States migrate shorter distances or not at all.

Or not at all.

And there was hope.